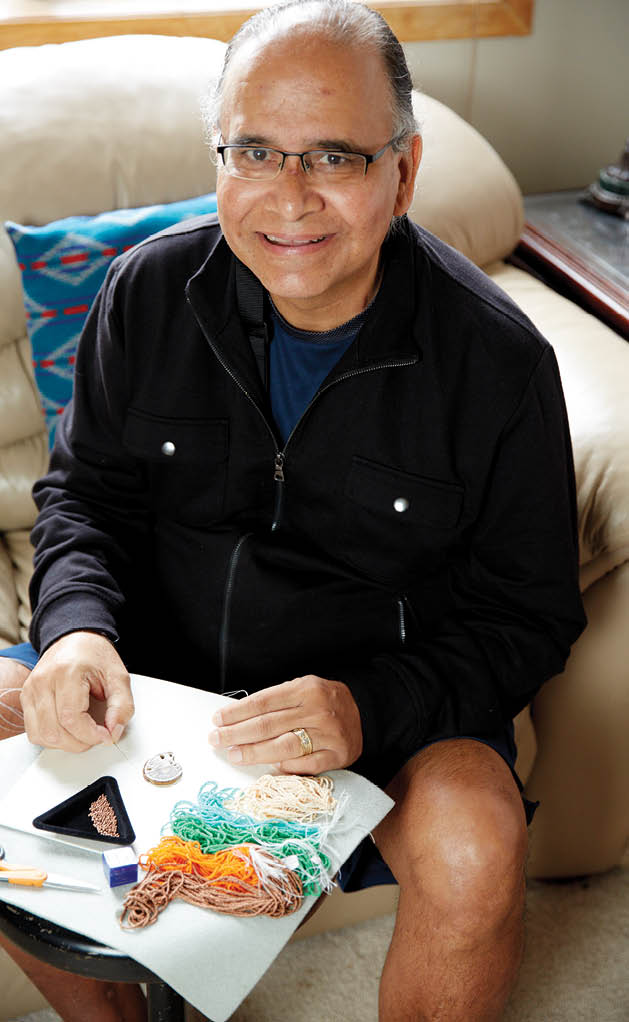

The first thing you notice at Doug Limón’s house is the turtles. Adorning a wall above the couch is a piece of art that features several images of large stingrays and turtles. There are beaded turtle images on wampum belts. And more turtles on his handmade cradleboard (baby carrier) and beaded medallions. What’s up with the turtles? Limón can explain. But we’ll get to that later.

This White Bear Lake resident has become an accomplished fine artist known for preserving his Native American heritage through beadwork on medallions, cradleboards and shoulder bags known as bandolier bags. An enrolled member of the Oneida Nation and a descendant of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe, Limón won his first award for a beaded medallion at an art show in Minneapolis in 2007 and has earned several awards since then.

The artist estimates he’s made about 150 round, beaded medallions, each 3½ inches across, and often adorned with a turtle design and buffalo-head nickel in the center. His pieces are used for Native American regalia, necklaces and wall art. “I don’t know how many beads I use in each one,” he admits. “We know how many size 11 beads are in a square inch; to find the exact number would make an interesting calculus problem.” Limón starts each beading session by burning sage as a way to honor his ancestors and ask them for help with the project.

Limón’s mother taught him how to bead on a loom at age 5, but he wanted to learn how to bead appliqué-style. “I would see this style at powwows. My parents bought me a book that showed the spot-stitch method of appliqué using two needles and two threads. But I later taught myself how to do it with one needle and one thread, a method I learned later is known as the straight-line method.”

Limón also recently started making bandolier bags. “I received a grant from the Minnesota State Arts Board in 2011 to do a community bandolier bag and did another one on my own,” he explains. For Native Americans, these bags traditionally carried tools, tobacco and traditional medicines. The beadwork often featured the plants or flowers needed for a specific medicinal recipe and often took a year to make. They could be used to barter for horses or other valuable commodities between tribes. To preserve this history, Limón’s grant brought him to the Science Museum of Minnesota at least once a week for a year to help visitors bead a community bandolier bag. “We had people from ages 4 to 70-plus participate,” he says. “Some did only one or two beads, others beaded a whole flower or other part of the design. It was a true community project designed to help visitors appreciate this Native American art form.”

Limón also teaches others how to make cradleboards to preserve another significant Native American tradition, and has taught classes, along with his wife, at Leech Lake Tribal College and Fond du Lac Tribal College. “Cradleboards have a lot of advantages,” he explains. “They help strengthen the baby’s legs, neck and back to promote early walking. They also help with language development as the babies are eye-to-eye with adults and can more easily associate language with actions.” Babies in cradleboards walk and talk earlier than babies who [aren’t in them], he says.

He proudly points out that his son Gavino (whose Ojibwe name, Mikinak, means “turtle”) began walking at nine months and at age 6 is already an accomplished Native American dancer. Gavino’s cradleboard, which features an elaborate beaded turtle fashioned with green concentric circles and purple flowers, is currently on display at the Science Museum. “My dad’s cradleboard classes have done the most to preserve our cultural heritage,” says Limón’s daughter Jaime Limón-Witt. “My dad has a passion to teach this craft to build cultural knowledge and pass on their health benefits so it doesn’t become a lost art.”

And for Limón, his exquisite art forms express his spirituality and honor his ancestors. “Oneidas believe in doing everything with the seventh generation in mind. Whatever we do today needs to positively affect people seven generations from now. I honor my ancestors through my work because they were thinking of me seven generations ago.” He says he always includes a flaw in his pieces, a practice his mother taught him to do as a reminder that no one is perfect.

The artist has earned the Minnie Jackson Lifetime Achievement Award from the Ziibiwing Center of Anishinabe Culture and Lifeways in 2012; the First Peoples Fund Jennifer Easton Community Spirit award in 2014; and the Cultural Community Partnership grant from the Minnesota State Arts Board in 2015. Thirty of his pieces were on display at the Minnesota Textile Center earlier in the year in a show called “Turtle Voices.”

So what’s with the turtles? “The turtle is old, wise and well-respected in our culture,” he explains. “And earth is often referred to as ‘Turtle Island,’ which comes from the Anishinabe creation story where the earth was formed on the back of a turtle.”